FULL INSIGHTS

This is a condensed version of our insights. Download the full version with additional research and materials.

Download

FACT SHEET

Download the factsheet “Why cities should consider congestion charging."

Download

Technical Director – Transport

Phil is passionate about working towards the vision of a safe and sustainable transport system for New Zealand that reduces harm to people and the environment and delivers a great legacy for future generations. His defining moments delivering transformational projects in the UK including Canary Wharf, London Bus and Tram projects, and transport planning for the London 2012 Olympics. In New Zealand, he has led the planning and delivery of the first phase of the AMETI project in Panmure, completed the business case for the Northern Corridor Improvements, and led the transport planning for the additional Waitemata Harbour Crossing. Currently, he is leading the Programme Business Case for road safety in Auckland.

Phil Harrison

Back to main

What worries me is building these safe routes and then tolling them risks leaving those with less disposable income (often driving older and less safe vehicles) using the free, but much less safe, alternative route. I don’t think this outcome sits comfortably within a Vision Zero philosophy.

The transport planner in me suspects that the answer to Auckland’s congestion issue, and a key way to decarbonise transport, is to implement congestion charging while utilising the income to continually improve other travel options. Depending on the details, this could either be a blunt hammer or a subtle knife. Some of the most obvious approaches to charging are potentially at odds with our civic responsibility to ensure fairness and equity within the system.

If the benefits of congestion charges aren’t evenly distributed over the population: some people will experience large improvements, whereas others end up with no appreciable improvements or even worse off than before.

The people that can pay will, but what of those that can’t?

Currently, NZ legislation doesn’t allow for congestion charging, only for tolling of new roads where a “feasible un-tolled alternative” exists. The income from tolls can only be used for the ‘planning, design, supervision, construction, maintenance, or operation of a new road’. Tolls under this law have funded the construction and operation of some high quality, safe-system compliant routes.

Fact box: Understanding Congestion Charging

- Congestion charging leads to behavioural responses from the traveller, including switching modes and changing travel times. However, unless the charges are very high, many car drivers tend to stay and pay.

- The congestion reduction effects and societal benefits of congestion charging depend on individual behavioural responses to price changes. A dynamic pricing system can be fairer and better achieve objectives than a fixed charge, but if too complicated can confuse users.

- It’s essential to have feasible alternatives for a wide range of road users. This may require substantial investment in other modes of transportation, before charges are imposed. Borrowing against future toll revenue to pay for these improvements is a possibility but risks overestimating the future income stream.

- The relationship between traffic demand and travel time is non-linear, which means it doesn’t require large reductions in traffic volumes to achieve substantial improvements in travel times – with the opposite also true.

- Private car use is underpriced in economic terms. People aren’t paying the full costs that private car use puts on society (such as emissions, safety, noise, road construction and maintenance, and congestion).

- In severe congestion, the capacity of the road can drop below its design capacity. By leaving demand unmanaged (no decongestion charging) we accept a lower level of infrastructure performance.

- When making travel choices, people take into account their own direct cost of travelling, but not the cost imposed on society

- Congestion charging is an effective instrument to capture societal costs in travel decisions and make the transport system more efficient.

“The transport planner in me suspects that the answer to Auckland’s congestion issue, and a key way to decarbonise transport, is to implement congestion charging while utilising the income to continually improve other travel options.”

Building a business case

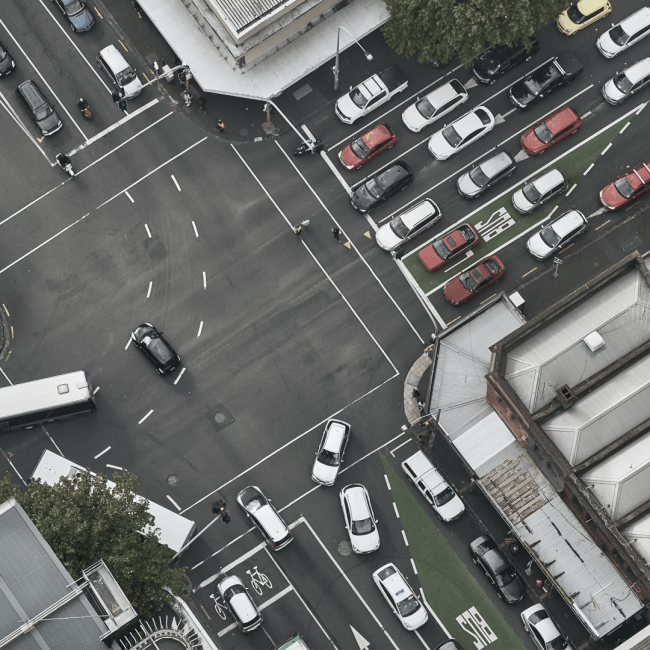

Cities that have implemented congestion charging have predominantly done so to reduce congestion and emissions. For a city like Auckland, the economic benefits of easing congestion are significant.

A 2017 report by the NZ Institute of Economic Research showed that if the average speed across the Auckland network was close or equal to the speed limit - known as free-flow – the benefits would be between $1.4 and $1.9 billion (between 1.5% and 2% of Auckland’s GDP).

By: Phil Harrison

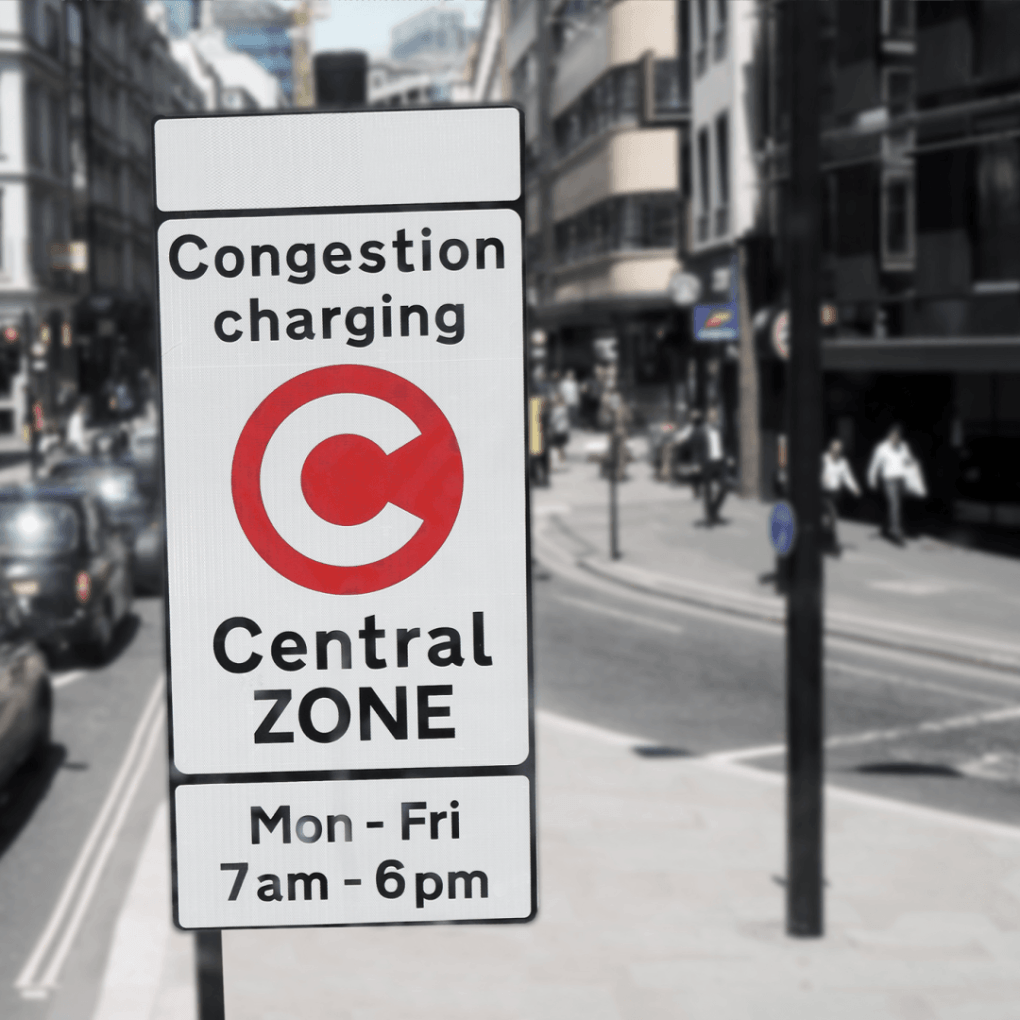

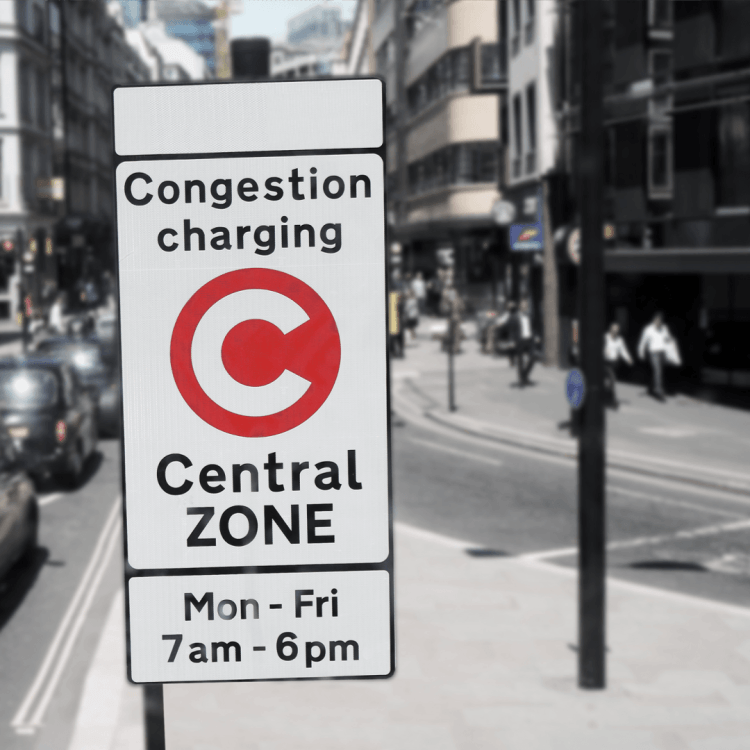

Congestion schemes in Singapore, London, and Stockholm have delivered a 10 -30% reduction in traffic within the charging zone and 10-30% increase in traffic speeds.

Interestingly, in London and Stockholm, the greatest shift was to public transportation, while in Singapore it was to 4+ carpools and to the shoulder time just before the start of pricing.

On paper, congestion charging makes perfect sense. It’s a way of harnessing the power of the market to swiftly reduce the problems associated with traffic congestion, such as emissions and delays to the essential movement of goods, services, and people, without the need for massive investment in new transport infrastructure.

However, it can be a political hand grenade and difficult to introduce given the low initial level of public acceptance. A number of congestion charge schemes investigated around the world have failed to be implemented because of public opposition, Edinburgh being a prime example. Opposition can come from those who feel over-taxed, while others oppose charging based on equity concerns and fairness. It’s fair to say that the assumption of initial public opposition is a major reason for lack of political support.

Traits that contribute to increased support include the extent to which individuals trust the intentions and abilities of political authorities, and their awareness and concern for environmental issues. Support for congestion charges can be expected to be related to trust in the government and the ability to design and manage a system – or use the revenue efficiently - and support for public interventions in general.

One solution to addressing traffic congestion and lowering transport carbon emissions is introducing congestion charging. However, while the benefits can be substantial, public acceptance can be a huge barrier. Here WSP Technical Director Phil Harrison looks at whether congestion charging could be a successful option to drive a decarbonising behaviour change.

Back to main

Back to top

PART 5

Decarbonising transport: is congestion charging the answer?

Back to main

Technical Director – Transport

Phil is passionate about working towards the vision of a safe and sustainable transport system for New Zealand that reduces harm to people and the environment and delivers a great legacy for future generations. His defining moments delivering transformational projects in the UK including Canary Wharf, London Bus and Tram projects, and transport planning for the London 2012 Olympics. In New Zealand, he has led the planning and delivery of the first phase of the AMETI project in Panmure, completed the business case for the Northern Corridor Improvements, and led the transport planning for the additional Waitemata Harbour Crossing. Currently, he is leading the Programme Business Case for road safety in Auckland.

Phil Harrison

FULL INSIGHTS

This is a condensed version of our insights. Download the full version with additional research and materials.

Download

FACT SHEET

Download the factsheet “Why cities should consider congestion charging."

Download

What worries me is building these safe routes and then tolling them risks leaving those with less disposable income (often driving older and less safe vehicles) using the free, but much less safe, alternative route. I don’t think this outcome sits comfortably within a Vision Zero philosophy.

The transport planner in me suspects that the answer to Auckland’s congestion issue, and a key way to decarbonise transport, is to implement congestion charging while utilising the income to continually improve other travel options. Depending on the details, this could either be a blunt hammer or a subtle knife. Some of the most obvious approaches to charging are potentially at odds with our civic responsibility to ensure fairness and equity within the system.

If the benefits of congestion charges aren’t evenly distributed over the population: some people will experience large improvements, whereas others end up with no appreciable improvements or even worse off than before.

The people that can pay will, but what of those that can’t?

- Congestion charging leads to behavioural responses from the traveller, including switching modes and changing travel times. However, unless the charges are very high, many car drivers tend to stay and pay.

- The congestion reduction effects and societal benefits of congestion charging depend on individual behavioural responses to price changes. A dynamic pricing system can be fairer and better achieve objectives than a fixed charge, but if too complicated can confuse users.

- It’s essential to have feasible alternatives for a wide range of road users. This may require substantial investment in other modes of transportation, before charges are imposed. Borrowing against future toll revenue to pay for these improvements is a possibility but risks overestimating the future income stream.

- The relationship between traffic demand and travel time is non-linear, which means it doesn’t require large reductions in traffic volumes to achieve substantial improvements in travel times – with the opposite also true.

- Private car use is underpriced in economic terms. People aren’t paying the full costs that private car use puts on society (such as emissions, safety, noise, road construction and maintenance, and congestion).

- In severe congestion, the capacity of the road can drop below its design capacity. By leaving demand unmanaged (no decongestion charging) we accept a lower level of infrastructure performance.

- When making travel choices, people take into account their own direct cost of travelling, but not the cost imposed on society

- Congestion charging is an effective instrument to capture societal costs in travel decisions and make the transport system more efficient.

Fact box: Understanding Congestion Charging

Currently, NZ legislation doesn’t allow for congestion charging, only for tolling of new roads where a “feasible un-tolled alternative” exists. The income from tolls can only be used for the ‘planning, design, supervision, construction, maintenance, or operation of a new road’. Tolls under this law have funded the construction and operation of some high quality, safe-system compliant routes.

By: Phil Harrison

“The transport planner in me suspects that the answer to Auckland’s congestion issue, and a key way to decarbonise transport, is to implement congestion charging while utilising the income to continually improve other travel options.”

Congestion schemes in Singapore, London, and Stockholm have delivered a 10 -30% reduction in traffic within the charging zone and 10-30% increase in traffic speeds.

Interestingly, in London and Stockholm, the greatest shift was to public transportation, while in Singapore it was to 4+ carpools and to the shoulder time just before the start of pricing.

Building a business case

Cities that have implemented congestion charging have predominantly done so to reduce congestion and emissions. For a city like Auckland, the economic benefits of easing congestion are significant.

A 2017 report by the NZ Institute of Economic Research showed that if the average speed across the Auckland network was close or equal to the speed limit - known as free-flow – the benefits would be between $1.4 and $1.9 billion (between 1.5% and 2% of Auckland’s GDP).

On paper, congestion charging makes perfect sense. It’s a way of harnessing the power of the market to swiftly reduce the problems associated with traffic congestion, such as emissions and delays to the essential movement of goods, services, and people, without the need for massive investment in new transport infrastructure.

However, it can be a political hand grenade and difficult to introduce given the low initial level of public acceptance. A number of congestion charge schemes investigated around the world have failed to be implemented because of public opposition, Edinburgh being a prime example. Opposition can come from those who feel over-taxed, while others oppose charging based on equity concerns and fairness. It’s fair to say that the assumption of initial public opposition is a major reason for lack of political support.

Traits that contribute to increased support include the extent to which individuals trust the intentions and abilities of political authorities, and their awareness and concern for environmental issues. Support for congestion charges can be expected to be related to trust in the government and the ability to design and manage a system – or use the revenue efficiently - and support for public interventions in general.

One solution to addressing traffic congestion and lowering transport carbon emissions is introducing congestion charging. However, while the benefits can be substantial, public acceptance can be a huge barrier. Here WSP Technical Director Phil Harrison looks at whether congestion charging could be a successful option to drive a decarbonising behaviour change.

De-carbonising transport: is congestion charging the answer?

PART 5